July 26, 2018

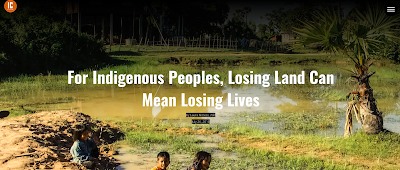

Ten years ago, the Cambodian government granted 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres) of land to a Thai company to plant sugarcane. But this land was not empty.

Six hundred families were already living on it, growing rice and vegetables and foraging food and other goods from the nearby community forest. Over the next few years, the company cut down more than half the forest. While conducting evictions, staff and security forces looted rice fields and demolished or burned more than 300 homes. Many people lost their land and all their belongings. Parents sent their children to work in Thailand, unable to farm and afford school fees.

Villagers are trying to recover some of their losses through a class action lawsuit. But even if they are successful, it will provide little remedy for the felled forests, destroyed homes and disruption of community life.

This story is all too common to the 2.5 billion people living on indigenous and community lands. These lands, crucial for livelihoods, are protected under international human rights law and social and environmental standards: Indigenous Peoples may not be relocated from their land without their free, prior and informed consent, and customary and informal land rights should be respected. Many national laws also incorporate these principles. However, because many communities lack legal titles to their land, governments may consider it empty and allocate it to companies. Corporations and others may consider the land to be idle or underdeveloped.

In reality, community land represents the backbone of rural life. Its loss—whether due to conflict, infrastructure projects, private investments or natural disasters—has grave consequences, including:

Loss of Livelihoods

Communities rely on collective lands for agriculture, livestock grazing and water. Community lands provide key foods, such as fish, game, honey and edible plants, as well as medicinal herbs, fuel and building materials. When displaced communities lose access to these resources, they may have insufficient space for traditional agricultural or grazing practices, such as letting land lie fallow. The result is decreased food security and increased stress on water resources.

Companies or governments may promise jobs and social services to displaced communities, but they seldom materialize. Jobs may be plentiful during the early stages of a project (for clearing land or building infrastructure), but they rarely translate into long-term employment. Small-scale farmers who lose land to larger projects experience an estimated 28 to 75 percent net loss in jobs.

Resettlement projects often cannot replace the loss of these resources. The experience of a Mozambican community, resettled from a protected area, is typical. The new location did not have sufficient space for agriculture and cattle, and community members did not receive promised jobs. Instead, they had to pay for water and food, which they had previously gathered for free from their land. Similarly, residents displaced by commercial farming in Zambia reported that their new land was infertile, they lost access to fish and game, and government-provided food aid was insufficient.

Increased Risk of Conflict

Community displacement places new pressures on surrounding land and resources, increasing competition and heightening the risk of conflict. This can create immediate tensions between communities, or re-emerge as an escalating factor in broader violent conflicts, such as in Kenya’s 2008 election-related violence, where grievances over displacement and land corruption fueled violence between political parties.

Similarly, two-thirds of all disputes between investors and communities in Africa occur where communities are displaced from their land. A study of 174 Indonesian palm oil companies found that land disputes were the primary driver of social conflict. In some cases, such conflicts are accompanied by violent encounters with security guards, threats and assassinations of community activists, or violent altercations when police or military enforce evictions.

Loss of Identity and Culture

For many communities, especially Indigenous Peoples, land is a locus of identity and culture as much as an economic resource. Displacement disrupts community structures and traditions, and means the loss of sacred and cultural sites. These intangibles can be irreplaceable: One mining company in Peru agreed to an unusually generous resettlement town for an Indigenous community, including paved streets, indoor plumbing and electricity. But three years later, residents complained of a lack of meaningful work and a loss of traditions. Rates of alcoholism rose, and in one year, four residents killed themselves by taking farming chemicals. According to one former farmer, the residents felt they were trapped “in a cage where little animals are kept.”

Similarly, in Canada and Brazil, some anthropologists link alarmingly high suicide rates in certain Indigenous communities to a loss of traditional lands. In Australia, Indigenous Peoples who live on their own land have a life expectancy 10 years longer than resettled communities. And after the Ecuadorean military evicted an indigenous village to make way for a mine, psychiatrists documented mental health problems in 42 percent of villagers, especially children traumatized by the noise of military helicopters.

Broader Environmental and Social Harms

Displacements from community lands can also exacerbate existing inequalities. Groups who are already marginalized are more likely to be displaced, and less able to advocate for their rights. For example, in India, Indigenous Peoples make up 8 percent of the population but constitute 40 percent of those displaced by development projects. Displacement has disproportionate impacts on women, whose use of collective lands are inadequately considered during resettlement.

Furthermore, large-scale land acquisitions that displace communities are primarily agricultural and mining projects, which require large amounts of water or cause deforestation. In contrast, Indigenous Peoples and rural communities are typically good environmental stewards. For example, in response to logging that was destroying their community forests, the indigenous Huay Hin Lad Nai village in Thailand set up a sustainable land and forest use system, including rules for restoring the forest and fostering traditional practices.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Projects that work with communities, instead of displacing them, can better accommodate a variety of land uses and avoid over-taxing natural resources. Communities also know how important their land is, and many are finding creative ways to protect it.

This article is the first installment of WRI’s Struggle for Land series. It was first published at WRI and re-published at IC under a Creative Commons License.

No comments:

Post a Comment